“Every person in Xinjiang is documented down to their genetic makeup, the sound of their voice, and whether they enter their homes through the front door or the back.”

By Sebastian Strangio

The Diplomat

August 24, 2021

In “The Perfect Police State: An Undercover Odyssey Into China’s Terrifying Surveillance Dystopia of the Future” (Public Affairs, 2021), American journalist Geoffrey Cain examines the reality of daily life in China’s Xinjiang region. Based on dozens of interviews with Uyghur exiles, the book illuminates how the Chinese government has pioneered a series of law enforcement and surveillance techniques, including data-enabled “preventive policing,” which have funneled hundreds of thousands into “re-education camps” and brought the region close to the reality depicted in George Orwell’s “1984.”

Cain spoke with The Diplomat’s Sebastian Strangio about the genesis of the Chinese government’s “slow, sinister erasure” of Uyghur culture, the complicity of Western tech firms, and the texture of daily life under the Party’s unblinking eye.

As your book reveals, the ethnic minorities of Xinjiang refer to the region’s regime of pervasive surveillance as “the situation.” What does “the situation” mean in practical terms for the average Uyghur or Kazakh? How and where does this system intersect with people’s everyday routines?

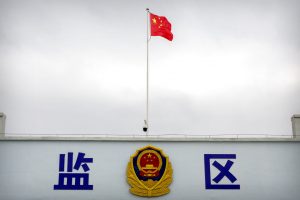

When Uyghurs and Kazakhs say “the situation,” they’re using a euphemism and codeword for all the surveillance that envelopes their daily lives. You can live your entire life in Xinjiang under the watch of the state.

Of course, other regimes have attempted this before. But what makes life in Xinjiang so foreboding is that the police have seized on new advances in artificial intelligence, deep neural networks, facial and voice recognition, and biometric data collection to establish the all-seeing eye. Every person in Xinjiang is documented down to their genetic makeup, the sound of their voice, and whether they enter their homes through the front door or the back.

I wrote “The Perfect Police State” because I wanted to show readers just how bad things can get. We live in an age where the unprecedented pace of technological advance has collided with the rise of authoritarians, strongmen, and major technology corporations with the muscle to overpower, or the cash piles to buy off, sovereign states. It’s a dangerous mix, and not one we should rule out coming to stable democracies in the West, too.

What was the genesis of the “perfect police state” in China? Why did the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) embark on this far-reaching project, and what is its ultimate goal?

Under the CCP, Xinjiang was always a far-off and restive region, with its own identity, language and culture distinct from the Han Chinese majority. And so Xinjiang was always the site of repression at the hands of the CCP, fearful that the region could break off and form its own nation. It’s what happened in the Soviet Union after its own collapse, with the creation of the states of Central Asia, such as Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

China was also concerned about terrorism in the region of Xinjiang – a small, radical segment of the population was bent on launching terrorist attacks against China. In 1996, China set up the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and signed up Central Asian nations for its mission to deter terrorist attacks and maintain security in the oil-rich regions of Eurasia. But it wasn’t until September 11, 2001 that China had a new impetus, a shield of “counterterrorism” with which to cover its repression of Xinjiang from criticism.

Ultimately, China’s goal was to create a total security state. It wanted to monitor, document, and surveil every square meter and every person in Xinjiang, buying its own propaganda that the region was teeming with terrorists. As one Chinese official in Xinjiang put it: “You can’t uproot all the weeds hidden among the crops in the field one by one – you need to spray chemicals to kill them all.” It sums up the CCP’s approach the region.

One strategy for creating a total security state is the absolute assimilation of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslim minorities – about 12 million people – into the ways of life of the Han Chinese majority.

This isn’t a genocide in the sense of the twentieth century, when fascist bureaucracies marched “unwanted” populations to death camps and forced them into gas chambers. This is the slow, sinister erasure of an entire culture, through psychological and physical torture at concentration camps, and never-ending surveillance that forces them to internalize the state’s thinking and deny their own realities.

It’s also the generational erasure of the population through forced sterilizations of women. By that token, under international law, China has committed genocide against the people of Xinjiang.

In your book, you describe the sheer pervasiveness of the surveillance state in Xinjiang, from the ubiquitous CCTV cameras to the use of data and algorithms in “preventive policing,” which have collectively brought the region into the realm of that described in Orwell’s “1984.” Can you give us a summary of what tools the Chinese government is using to police the minority populations of Xinjiang?

In addition to “1984,” life in Xinjiang reminds me of the Tom Cruise film “Minority Report,” based on the short story by the sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick, who also wrote the classic book that inspired “Bladerunner.”

Xinjiang runs a “predictive policing” program that uses AI, camera technologies, big data, and algorithms to crack down on its people. If the system believes you will commit a crime in the future, for whatever arbitrary reason, you’re in danger of getting a visit from the police and being taken to one of hundreds of known concentration camps. Without being charged with a crime, you’ll be brainwashed into “cleansing” your mind of “ideological viruses” and “cancers.” That’s literally the language that the Xinjiang authorities use.

For China to build its all-seeing surveillance state, it needed new advances in technology that converged around the same time period. The first was the hardware switch from the old analog CCTV cameras of the 1990s and early 2000s, and the shift to digital, where China led the way with state-run firms like Hikvision, the world’s largest maker of surveillance cameras.

The second breakthrough covered the interconnected fields of deep neural nets, facial recognition, and voice recognition in the early 2010s. New AI software had abandoned old algorithms and could now learn and train its own algorithms from vast amounts of data, gathered through cameras, clicks and purchases. Microsoft, Amazon and Chinese firms Megvii and SenseTime led the way, eager to monitor customers under the profit motive.

Do you think the CCP’s anathematization of Islam is a product of its ideology and history, or does it also reflect older patterns of interaction between the Chinese state and the empire’s Muslim populations?

I think the approach to Islam within its own borders, comes from ideology and recent history under the Chinese Communist Party. When we go back before the communist takeover, China had structured a different and more open set of relationships with Muslim populations in Central Asia and along the Silk Road.

Party apparatchiks will say differently. But China was not a dominant hegemon over Eurasia for much of its history. Its imperial court didn’t hand down edicts to a ragged and impoverished “Muslim world.” The silk roads were replete with cosmopolitan and prosperous empires, many of them Muslim, and China traded with them, and made enemies with others.

Eurasia would have looked more like Europe, with scattered identities and languages and people, that traded and fought. Claiming that China has an ancient, imperial lineage over Central Asia would be like arguing ancient Rome, the Renaissance and Mussolini are all a line of continuity to Italy now, or the 19th century German Romantics inspired the rise of the Nazis.

Mulan, the legendary figure, would have probably been Turkic, not Han Chinese, with a heritage closer to the Uyghurs and Kazakhs of today. Zheng He, the famed Chinese seafaring explorer, was Muslim, built mosques, and was key to connecting China with Muslim nations. The Qing dynasty, in the 19th century, wasn’t all that interested in Xinjiang, finding control too costly. The fact is that what we envision today as “China” is really just a collection of disparate peoples, including Muslims, who happen to be blanketed under the aggressive, colonizing force of the CCP.

In recent years, the Uyghur human rights issue has become wrapped up with broader strategic tensions between China and the United States, which makes it even less likely that the Chinese government will take U.S. concerns on board. What, if anything, can concerned foreign governments and individuals do to address the situation in Xinjiang?

Because of sanctions, Chinese officials are terrified of the possibility that their assets in the U.S. and in the European Union could be exposed. But corporate transparency hasn’t been a strong point in the U.S. system, and in the Caribbean where tax havens are typically under British control. We’re more than happy to host the dirty money of foreign kleptocrats as long as we can take a cut.

Many abuses come down to forced labor in global supply chains. Reforming the global offshoring system would be a strong way of pulling out the rug from underneath the CCP’s human rights abusers.

The U.S. and U.K., in particular, need stronger laws that require real-name registration on corporations that would open the door to exposing and freezing the holdings of CCP kleptocrats. The sanctions so far haven’t been enough. By going after individual companies and people, they attack a symptom, not the problem. The CCP’s human rights abusers get away with a lot, stashing their dirty money in the West, because Western law enforcement authorities are hamstrung from seeing who owns what in a transparent way.

See Also: