By Geoffrey Cain

PRI’s The World

Jan 8, 2015

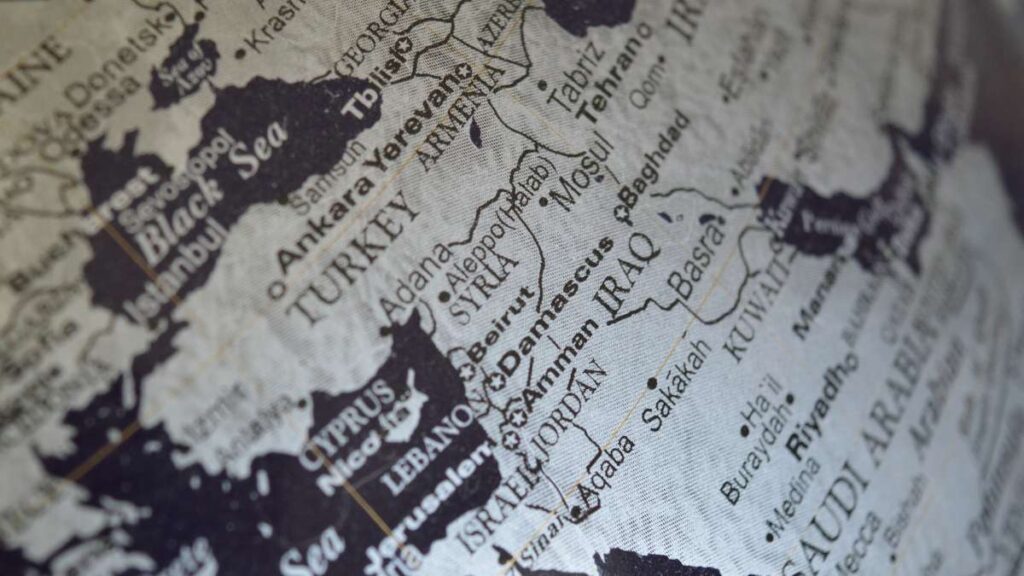

SEOUL, South Korea — Is change brewing in North Korea, one of the world’s most totalitarian nations?

At first glance, it would seem unlikely. For more than two decades, the fortress-like regime has evaded predictions of collapse and chaos, surviving war, famine, and economic ruin. It has mystified the world with its ability to stay put — despite its nuclear brinkmanship and naval skirmishes with neighbors.

Since the late 1940s, the dynasty of three Kims (with the third one, Kim Jong Un, now in power) has averted any possibility of revolt. Adversaries have been sent to prison camps, with their family members purged. Prior bouts of optimism for reform have been short-lived.

North Korea’s regime, in other words, has mastered the art of control.

But under Kim Jong Un, a pair of edicts — the first reportedly issued in 2012 and then expanded in 2014 — could be pushing the country into the early stages of an economic shake-up, potentially placing North Korea on the path to Chinese-style reform.

At least, that’s the bold conclusion of Andrei Lankov, a renowned North Korea expert at Kookmin University in Seoul who studied in Pyongyang as a young man.

The plans, the latest of which is called the “May 30 Measures” (named after the date it was passed in 2014), give farmers more control over their harvests so they have an incentive to ratchet up food production. This year, farmers will reportedly get 60 percent of their total harvest rather than the 30 percent allotted to some in the 2012 experiment.

Factory directors will also get more freedom to choose what they buy and who they sell to, according to Lankov.

Lankov says he hasn’t seen the document, but has gleaned its contents from interviews with Chinese and North Korean sources.

The changes may sound obscure, but as a respite from strict central planning their impact could prove huge — changing lives and invigorating the economy.

In 2013, around the same time the first reforms went into effect, the harvest was relatively strong. There are other signs: Last spring, North Korea was hit by a severe drought that Lankov contends could have easily caused famine, a scourge that killed hundreds of thousands in the 1990s.

But since the bad weather yielded no evidence of devastating food shortages, he believes the harvest has kept apace. “There were no worrying trends,” Lankov said. “The economy has been improving.” He expects the next stretch of reforms to start early this year.

Sources who work regularly with North Korean refugees agree that the food situation has been getting better and that the latest policies, if true, could amount to something important.

“North Korea is still a terrible place, but for a while we’ve had this sense that there are changes happening in the society,” said one Christian missionary who covertly assists North Korean refugees in China. He asked not to be named, citing the presence of Chinese agents near the border.

“People get their food and just about everything on the black market,” he said. “They aren’t as dependent on the government anymore, and that is why I think Kim Jong Un probably approved these reforms.”

Lankov is the first scholar to suggest a potential thaw in hard-line central planning. Others are skeptical. The South Korean Unification Ministry, which oversees relations with the North, sees no evidence that the reform plan even exists. Others say any causal link between policy and a more bountiful harvest is tenuous at this early stage.

It’s also unclear whether the changes would be sufficient to stabilize North Korea — a cold, mountainous country prone to bad harvests — with tragedies worsened by backward state planning.

An estimated one in four North Korean children may be chronically malnourished, and 4 percent acutely malnourished, according to the United Nations humanitarian agency, UNOCHA. Meanwhile, UNICEF believes that one in 10 North Korean children are severely stunted.

Moreover, it remains uncertain whether the supposed changes would mark the first in a long series of reforms, of the type that lifted the burden of poverty for millions in China. A decade ago, the mercurial regime embarked on a liberalization of its socialist food distribution system. The changes were soon reversed, and the prime minister behind them temporarily relieved of duty.

The article was originally published in PRI’s The World

See Also: