The Korean giant pumped billions of dollars into China and came to dominate its smartphone market. Now, it’s closing factories. What happened?

By Geoffrey Cain

The Wire China

November 1, 2020

It was a stifling hot July day in 1992 when Qian Qichen, China’s foreign minister, took a helicopter to the lakeside villa of Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s leader. Qian was used to uncomfortable situations — he had sparred with Brent Scowcroft three years earlier after the massacre at Tiananmen Square — but this trip was uniquely sensitive. Qian’s task was to deliver a message to Kim from his boss, Jiang Zemin, explaining that China had decided to establish diplomatic relations with South Korea — a country that, at that point, wasn’t even shown on the maps produced in China.

It was a shocking betrayal. The Korean War enemies didn’t exactly see eye-to-eye: China saw South Korea as the traitorous neighbor that had resisted communism and fled into the arms of America, and South Korea saw China as an aggressive invader that should not be trusted. But following the end of the Cold War, China and South Korea emerged as awkward trading partners. And as South Korea’s economy pulled further ahead of North Korea,1 China realized it needed to adjust course.

According to Qian’s memoir, the then-80-year-old Kim listened quietly before announcing that his country’s friendship with China would overcome all difficulties and North Korea would continue to “build socialism.” Impressed — and no doubt relieved — by the old leader’s reaction, Qian was back in Beijing that same afternoon. A month later, Qian hosted South Korea’s foreign minister for their first public appearance together. Sitting at a long green table, the men signed documents to officially normalize the China-South Korea relationship.

Given the political betrayals involved — North Korea on China’s side, and Taiwan on South Korea’s side — this decision was about business. After Deng Xiaoping came to power, China began relaxing its ideology and moving towards a path of pragmatism, hoping to dig out of poverty. South Korea offered a shovel. With dictatorial policies of industrial control, the once poor and barren country of South Korea had emerged as an industrial center in only 30 years.

Now South Korean firms saw big opportunities in China thanks to its huge market and cheap labor.

“It was South Korea pointing across the sea and saying, ‘That’s our future,’” says Mark Clifford, author of Troubled Tiger: Businessmen, Bureaucrats and Generals in South Korea.

Days after Qian hosted the South Korean delegation, Samsung, South Korea’s biggest company, christened a new factory in Huizhou, in southern China. Samsung had been so integral to South Korea’s own growth that people joked the country should be called the “Republic of Samsung.” Eager to learn, China wooed the electronics company with favorable terms and early access to its fertile, untapped market. The result was a fast and fruitful love affair — and the Korean corporate giant went all in.

Soon after, Samsung plowed billions of dollars into China and built facilities to manufacture VCRs, music players and printers for export. It set up R&D facilities in coastal cities like Shenzhen and Shanghai, a semiconductor plant in Suzhou, and display factories in Tianjin and Shenzhen. By 2005, 57 percent of Samsung’s global revenue was derived from its Chinese operations.

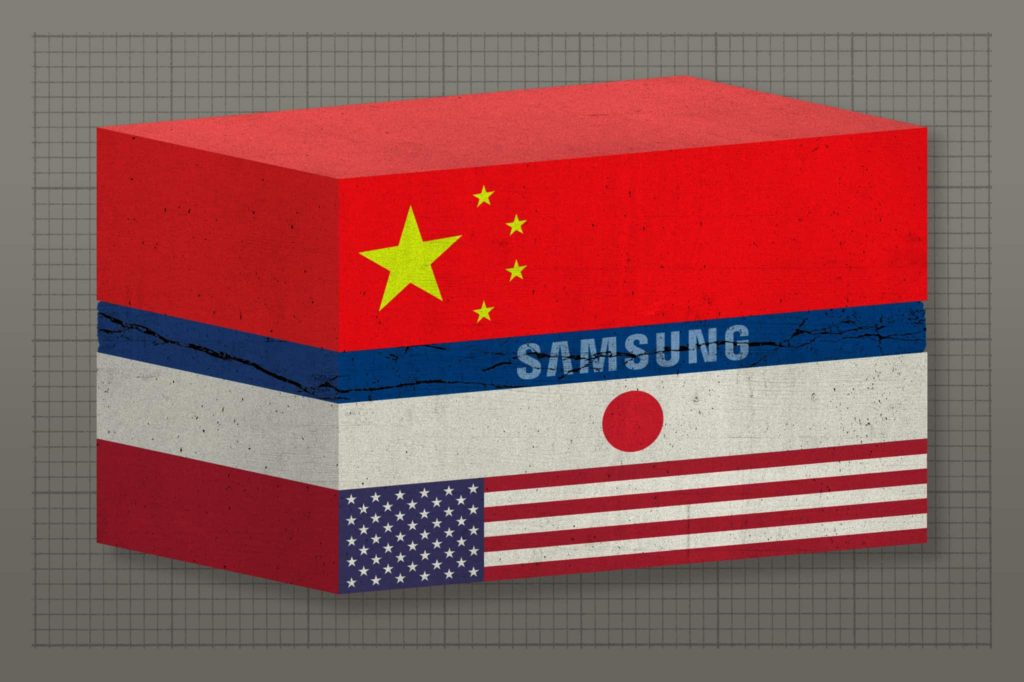

There were signs of trouble, however, in 2007. That year, Lee Kun-hee, chairman of the Samsung Group, warned in a speech that South Korea was caught in a “sandwich” between advanced economies that dominate the high-end market and Chinese manufacturers that were quickly catching up. “I am more worried about the next 20 years to come,” he said at a speech at Samsung’s Shilla Hotel. “In a situation where China is catching up and Japan is taking the lead, Korea finds itself in a sandwich situation. If we do not overcome it, we have no choice but to greatly suffer. This is the position of the Korean peninsula.”

Lee, who died last Sunday at the age of 78, thought the republic of Samsung could innovate its way out of the problem, but China had other plans. Indeed, as China’s economy boomed and its technological capabilities grew, foreign firms began complaining about stricter regulation, forced technology transfers and stiffer competition from Chinese firms. Some global brands, like Samsung, now see the situation as untenable.

With China likely to become the world’s largest economy by 2025, Samsung has retreated from two of its three core businesses in the country. Seven months ago, the company announced it was exiting the LCD display business. And a year ago, Samsung closed its last mobile phone factory in China and shifted production to Vietnam and other lower cost regions.

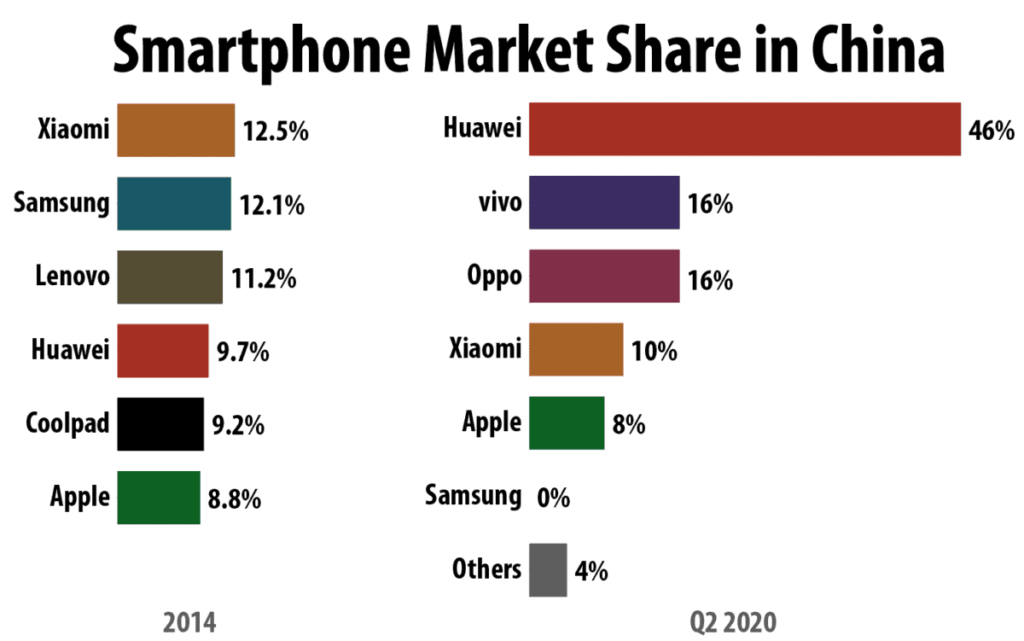

The reversal is hard to fathom. Samsung, which did not respond to requests for an interview, was the dominant mobile handset maker in China a decade ago. Today, with a negligible share in a market dominated by Chinese firms, Samsung is basically calling it quits in China in the mobile phone business.2

“There’s political logic behind Samsung moving out,” says Sungmin Cho, who teaches at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii. “The Chinese government is discriminating against foreign firms, and it’s not transparent about intellectual property rights. China’s becoming more unpredictable.”

As one of the first multinationals to build a huge presence in China — the company has invested more than $20 billion in the country — the departure of some of its core business lines is as dramatic as its 1992 entrance. It could also be telling. With political uncertainty, sanctions, trade wars and rising labor costs in China, could its moves hint at the prospects of other global brands?

FROM STRETCHED TO SQUEEZED

When Chairman Lee died last week, his passing marked the end of an era of growth and globalization for Samsung. After the end of the Cold War, Lee devoured documentaries, films and books from his home perched on a hill overlooking Seoul, and became convinced the world was undergoing a tectonic shift. At the time, Samsung televisions and microwaves had dominant market share in South Korea, but Lee realized this wasn’t enough in the new world order. Globally, Samsung products were known to break down and were generations behind their Japanese and American competitors. On a 1992 trip to Los Angeles, for example, he saw Sony televisions on the top shelves of a department store and Samsung on the bottom.

Samsung had already cut its production costs by moving production to China. But Lee sensed that Samsung would have to do better in high-end consumer markets. Lured by attractive deals and tax breaks, he threw Samsung’s R&D into China as well, hoping to develop advanced semiconductor and display technologies.

“Change everything except your wife and children,” he told a room of Samsung executives in 1993 during a speech that became a part of the company lore. Two years later, he organized a bonfire, ordering employees to gather $50 million worth of faulty cell phones and other electronics, throw them into piles, hammer them, pour petroleum over them and set them on fire. A bulldozer razed whatever remained, to drive home the Chairman’s point.

“Change everything except your wife and children.”

-Chairman Lee Kun-hee, in a famous 1993 speech to executives motivating them to overhaul the company

Samsung’s commitment to developing high-end technologies was communicated to its employees as a fight against complacency. Although the company relied on factories in China, its new vision of “perpetual crisis” borrowed its urgency from South Korea’s historical paranoia about being caught between great powers. A Samsung comic book distributed to employees in 1994, for example, depicted Chinese and American villains ganging up on an unsuspecting Korean aristocrat. It also showed a map of South Korea, which appeared geographically small and vulnerable, next to the behemoth China and powerful Japan. “How miserable it is to become a country that is economically subordinate to other countries,” the book told executives. It urged them to prepare for the coming fight.

Despite positive moves in two key technologies — semiconductors and displays — Lee pushed for a relentless expansion into automobiles, PCs and even the film industry. Then, in 1997, South Korea’s debt bubble popped in the Asian Financial Crisis. Frantic for new opportunities, Samsung doubled down on mobile phones. The company had recently secured a deal supplying mobile phones to Sprint, in the U.S., but now executives looked at the vast, untapped markets of middle-income countries. Suddenly, their operations in China looked like more than just cheap manufacturing.

“China had so many people, so many potential consumers,” says a former Samsung phone designer who was involved in the phones developed for Chinese consumers. “We could sell the premium phones on the American market, but we could sell so many more low-end phones to the Chinese market.”

At the time, Chinese-made phones were laughable. China was home to knock-offs that dropped calls and broke. So Samsung competed with Nokia, a low-end Finnish phone maker at the time. With operations already in China, Samsung stumbled upon a winning approach. Known as gaeseon in Korean, Samsung released quick bursts of hardware innovation. High volumes of Samsung phones, TVs and other devices were everywhere, with seemingly endless options of colors, sizes and form factors. For China, variety was tantamount, and Samsung quenched the desires of Chinese customers who wanted the ability to tinker with software and hardware, replace parts, and even resell altered handsets.

Credit: Kprateek88, Creative Commons

By 2005, Samsung dominated China’s consumer market with $7.8 billion in revenue. The cash infusion helped shore up its semiconductor operations in China, which was critical in Steve Jobs’s decision to use the Samsung flash memory chips manufactured there in his iPod shuffle, iPod nano and then-upcoming iPhone. Known as “frenemies” in the tech sphere, Apple and Samsung had both cooperative and competitive businesses, but the iPhone’s debut, in 2007, hardly made a dent in Samsung’s domination of China’s consumer market.

The opposite of gaeseon, Apple released one premium product at a time. Still, Samsung followed in 2009 with its own premium smartphone, the Galaxy, using Google’s Android software. By 2011, Samsung controlled a third of the smartphone market in China — three times Apple’s market share.

But while Samsung was doing well fighting off competitors from above, the squeeze from below was on. In 2011, a Chinese startup named Xiaomi released its first phone. Two years later, even as Samsung was posting record profits and producing one out of three of the world’s smartphones, its stock price tumbled. Investors pointed to inroads made by Xiaomi. By 2014 the Chinese startup had edged Samsung out its top spot in China.

“If you look at Samsung’s experience in China with smartphones, it hasn’t been particularly good,” says Alex Capri, visiting senior fellow at the National University of Singapore Business School. “If Samsung was thinking about a short-term gain or profit by providing this kind of tech to China, they have to understand that eventually when the Chinese can do it themselves, they will push [Samsung] out.”

Data: International Data Corporation (2014); Counterpoint Research (Q2 2020)

Chairman Lee wouldn’t see his prophecy of the Samsung sandwich come true — that year he suffered a heart attack and disappeared into a hospital in a vegetative state. But his son and presumptive heir, Jay Lee, did. In July 2014, during a Chinese state visit to South Korea, Jay attended a lecture that Xi Jinping gave at Seoul National University and noted the change of tone. “I think China does not need to study Korea anymore,” he said. “I felt the country’s potential is enormous.”

As Chinese startups continued to capture the local market, Samsung’s shipments in China plummeted. Then came the infamous battery debacle. In September 2016, Samsung instigated a sweeping $1 billion recall for Galaxy Note 7 phones after reports that its lithium ion batteries were igniting in the hands of its customers. After recalling the phones, and issuing replacement phones that also ignited, Jay Lee called his top lieutenants and cancelled the product.

“The worst event [for Samsung in China] was the battery explosions,” says Peter Li, who teaches at Nottingham University Business School China. “Samsung never recovered from that incident.” That year, Samsung’s smartphone market share in China fell below 5 percent and then plunged more. Meanwhile, Apple grew to 9 percent and the Chinese companies Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, and Xiaomi together ballooned to 66 percent. The South Korean company was again stuck in that awkward middle ground.

“The one thing to learn is that you either command high prestige and appeal like Apple, or adapt to what local customers prefer,” Li adds. If you don’t, “the two sides squeeze you, and then you are out.”

Credit: CGTN

THE CLOCK IS TICKING…

Though China’s economic relationship with South Korea looks vastly different today than it did in 1992, its political relationship is, in some ways, more similar than ever. In the mid-2010s, the South Korea government agreed to host the U.S.-operated THAAD missile defense system3. The system was ostensibly aimed at shooting down incoming missiles from North Korea, but Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi noted that the system jeopardized China’s “legitimate national security interests.”

While this was another instance, in China’s mind, of South Korea turning to its American defenders, China had new tools at its disposal. The THAAD system was set to be installed on a golf course owned by the Lotte Group, a prominent South Korean retailer, which had a huge presence in China. Since 2004, Lotte had invested $9.6 billion in China. In retaliation for its part in the missile defense system, China instigated a sweeping boycott and shut down its Lotte stores in China. Within days, Lotte became a scapegoat for a rising tide of anti-Korean rage in China. “F-ck Korea,” read one English-language sign hanging over a Beijing restaurant at the time.

Lotte Mart, the group’s department store, lost $850 million in the year after South Korea decided to deploy the THAAD anti-missile system. By the time China lifted its sanctions on Lotte in mid 2019, the damage was done: Lotte shut down its entire chain of 112 stores and four of six factories, ending its reign as a nameplate department store in China.

Samsung executives watched the affair with alarm. “That’s when we realized that we had to think carefully about our next steps in China,” says one former Samsung vice president in the semiconductor division. “Before [the Lotte affair], the stakes were lower. China might retaliate against something it didn’t like by raising the tariff on phones, just to give a hypothetical, but we could always do okay with those tariffs. But now, China showed that if it didn’t like you, it would pursue you, and destroy your entire business.”

Witnessing the Lotte disaster, Samsung executives called a series of meetings to assess the future of their investment strategy in China. Despite record profits that year, Samsung continued a longterm strategy to “diversify” its operations, by moving phone and display manufacturing to Vietnam, Indonesia and India for cheaper labor. But the company doubled down on memory chips, which China still desperately needs, agreeing to spend billions to expand production in the city of Xi’an.

Samsung and two other companies — South Korean semiconductor manufacturer SK Hynix and America’s Micron — control 95 percent of the global supply for DRAM chipsets that power smartphones and computers. Since 2000, with the founding of Chinese semiconductor giant SMIC, the Chinese government has been encouraging its companies to make their own chipsets in order to bring down prices and ensure a stable supply. Memory technology marks the most pronounced area where China still lags, but Samsung is worried about losing its edge.4

“Samsung’s biggest concern is that its reliance on memory products will become too large,” says Joo Wan Lee, research fellow at the POSCO Research Institute, a think-tank in Seoul.

Samsung has also exited another industry it long dominated: LCD displays used in smartphones and televisions. Samsung supplies half of the world’s smartphone displays. But last March, Samsung said it would stop making LCD displays at the end of the year, apparently because of surging Chinese supplies, analysts say.

“Korea is unable to compete with China’s low prices for raw materials,” says Chung In-jae, a former CTO at LG Display America, a Samsung competitor. “With its government support and subsidies for the display industry, China’s strategy is to pin down South Korea. If Korea sells raw materials for displays at 100, China will say, we’ll give it to you for 90 or 85.”

Credit: Samsung Newsroom, Creative Commons

In August, Samsung sold its display plant in Suzhou to a Chinese display maker owned by TCL. Samsung will close its only television plant in Tianjin this month. Squeezed out from below, it’s hoping to find some breathing room above with a newer, better display technology called QLED, in South Korea.

It’s following the same strategy with 5G data networks. Samsung controls about 15 percent of the global 5G equipment market, according to Dell’Oro. In September, it won a $6.6 billion contract with Verizon to supply 5G equipment in the U.S. until 2025 and is working on a next generation 6G network.

But some observers aren’t so certain that Samsung will find a way out of the sandwich that Chairman Lee predicted 17 years ago.

Credit: Samsung Newsroom, Creative Commons

“South Korea is still stuck in the middle, and its industry structure does not offer a clear way out,” says Ulrike Schaede, who teaches at the University of California, San Diego. China, she notes, already owns the low-end assembly process and is moving into components, such as batteries, and Japan, the U.S., and others still control “many of the critical, deep-tech input materials” that Samsung needs. (Samsung is also investing in electric battery production in China.)

Feeling the squeeze, Vice Chairman Jay Lee is hoping to inspire the same level of urgency his father did 20 years ago.

“We are in a situation facing severe risk,” he said at a chipset R&D plant in Hwaseong, South Korea, in June. “Our survival depends on how fast we can secure future technologies. We do not have much time.”

Grace Moon and Wen-yee Lee contributed reporting

The article was originally published in The Wire China

See Also: